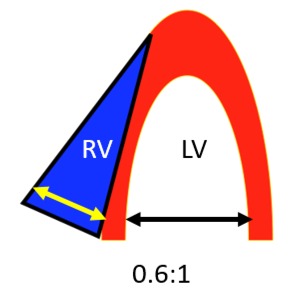

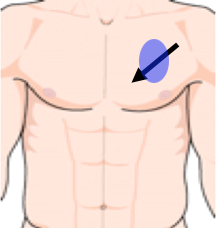

E is for Equality

- Is RV as big or bigger than LV?

- Normal ratio ~0.6:1 (in A4C)

- 1:1 or greater is definitely abnormal

-

Acute symptoms – possible pulmonary embolism (PE)

- Not perfectly sensitive (small PEs)

- Not perfectly specific (RV strain from COPD, etc.)

Narration

The third E is for equality and this is really trying to estimate if the right ventricle is as big or bigger than the left ventricle. So normally the RV:LV ratio should be about 0.6 to 1 and this is classically measured in the apical four chamber view across the tips of the valves. We choose 1:1 as being abnormal because if you're getting the view correctly, it’s definitely abnormal when the ratio exceeds 1, when the RV is equal to or greater than the LV. We use this to really tell us if someone with acute symptoms such as shortness of breath or chest pain may have a pulmonary embolism. Large PEs will show signs of right ventricular strain and can be a big help in terms of diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy. Keep in mind however, that right ventricular strain is not sensitive for PE because you can certainly have small PEs that don't show any signs on echo and it’s also not perfectly specific in the sense that you can have RV strain from more chronic conditions such as COPD, pulmonary hypertension, things like that.

-

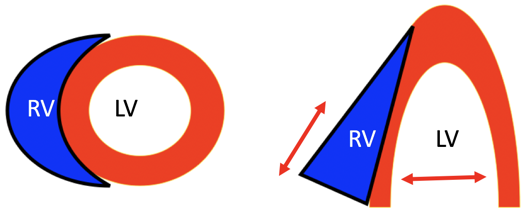

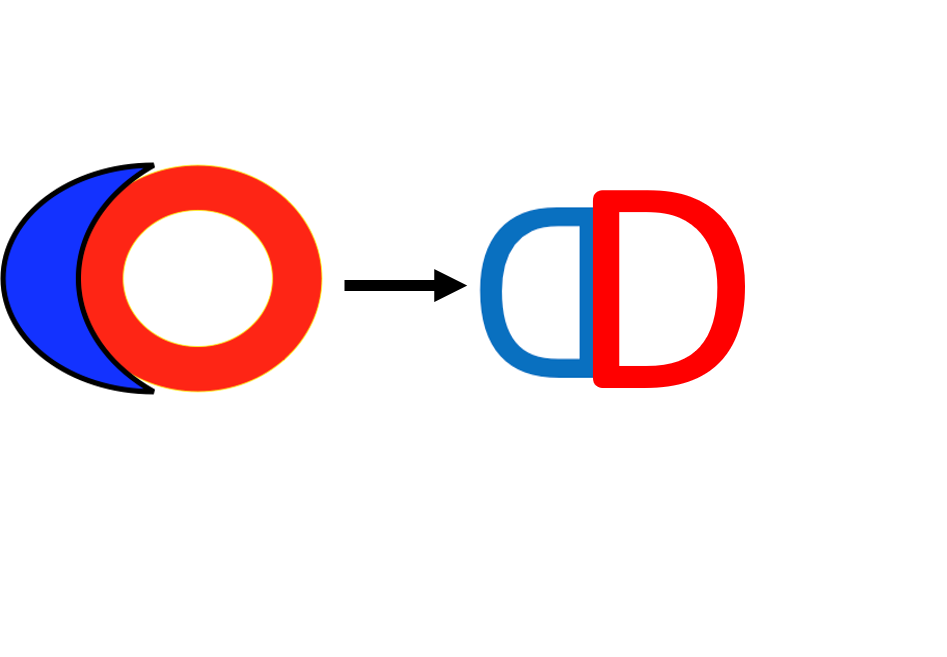

RV geometry

- Thin walled

- Crescentically wrapped around LV

- On parasternal short axis normal LV is a circle, no septal flattening

- Note movement from base to apex of right heart (vs. squeeze of LV)

Narration

So the RV is a thin walled somewhat crescentic shape chamber that wraps around this circular, muscular thick walled left ventricle. If you look at it in short axis you'll see that LV has a circle with the RV as an after thought in the upper left corner of the image. When you look at it in apical view, you'll see the right side of the heart on the left side of the screen as it is viewed. One thing to note on this is that the right ventricle contracts from the base to the apex and you can see vigorous motion of the lateral part of the tricuspid valve in a normal RV. This is as opposed to the left ventricle which really contracts circumferentially along the long axis from side to side rather than base to apex. So keep an eye on that in terms of how well the right ventricle is functioning.

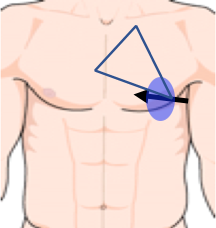

- Parasternal short axis

- RV strain produces septal flattening

- "D shaped" septum

Normal

RV Strain

Narration

So I tend to think that the parasternal short axis is one of the best ways to tell if there is significant right ventricular strain or if the RV is equal to or greater than the LV. The normal parasternal short axis shown in the lower left pane shows this circumferential left ventricle squeezing all the way around with the right ventricle again on the upper left part of the screen but really not pressing in on the left ventricle. This is contrasted to the image in the right upper part of the screen here where we have a very dilated right ventricle that’s pressing in on the septum and actually compressing the left ventricle you can barely get any blood in there because it’s so compressed on the right side. The short axis can be a good way to look at this. We'll talk about the "D" shaped septum which is basically how the right heart presses in and flattens the septum so that it looks like a "D". That's the image that we have on the right up there, showing the septal flattening or D shaped septum.

Parasternal short axis RV strain

Narration

So here is another example where we see the RV and the LV. The RV is very dilated and the septum is flattened, and it appears to be like a "D" and again the parasternal short axis is a very good way to look for significant right ventricular strain.

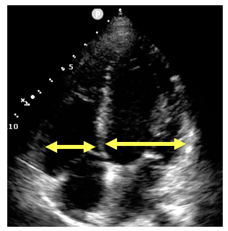

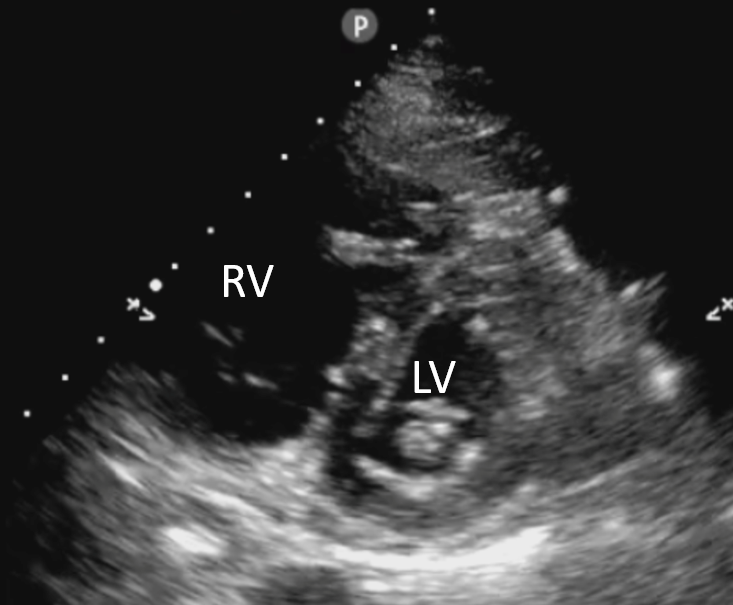

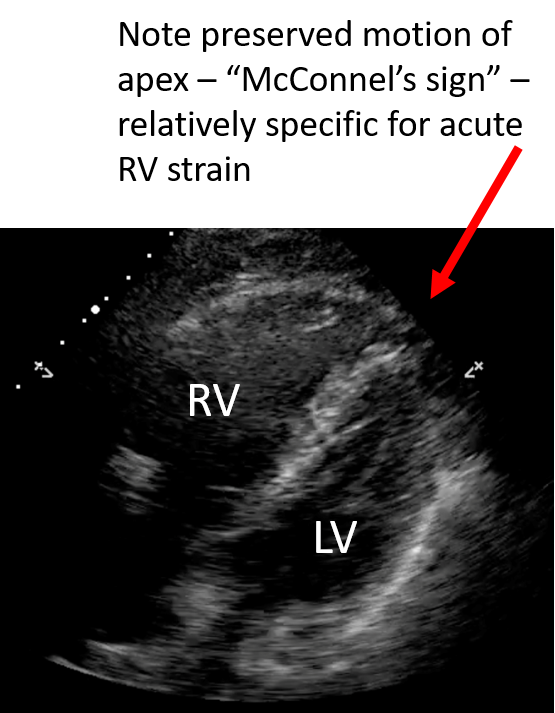

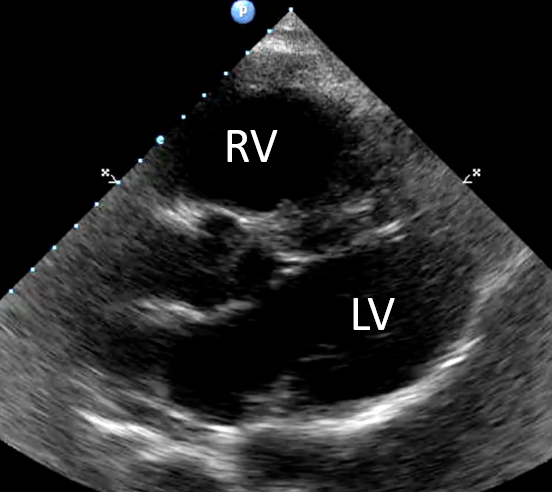

Apical 4 chamber RV strain

Narration

The apical four chamber is also really good if you can get it - this image shows an apical four, it's somewhat medial so the septum is at a bit of an angle, but you can tell that the right ventricle, which is on the left side of the screen as we're viewing it, and also anterior is markedly dilated when compared to the left ventricle. The other thing to note on this particular image is that while the mid portion of the right ventricle is dilated and not contracting well, the apex is actually doing quite well and this is something called "Mcconnel's Sign" which is fairly specific for acute right ventricular strain as opposed to chronic RV strain from COPD or pulmonary hypertension. So when you see overall hypokinesis of the RV with apical sparing, that is more indicative of an acute RV strain process such as a pulmonary embolism.

- PSLA RV strain

- Beware - angle may enlarge RV

- Attempt to maximize LV

- Note decreased septal movement

Narration

You certainly can pick up RV strain on other images such as the parasternal view, and this is one image here on the upper right that does show significant RV dilation it is very prominent in the anterior part of the screen and if you look at the septum its being pressed somewhat into the left ventricle. I would caution you to be a little bit careful with the parasternal view, because depending on how you angle it you may make the right ventricle look a little bit bigger relative to the LV, so you really want to maximize that left ventricular size and see if the RV does look like its straining or pushing into the left ventricle on the parasternal view.